Harvard China Fund in Action

Along a wooded path, Ned Friedman is pointing out trees whose DNA originated in China: “A Chinese ginkgo,” he says, in front of a tree exploding with bright yellow, fan-shaped leaves. “We have one of the finest collections of ginkgoes from China in the world.” And then a rare maple species that originated in Gansu, China. Then a Chinese plum yew, collected in 1980. And a Chinese witch-hazel, Hamamelis mollis—“wild collected” in Wudang Shan, Hubei, in 1994 as part of a North America–China Plant Exploration Consortium expedition. “Other than North American trees, our second biggest collection comes from China,” Friedman says. “This is literally where people come to study Chinese trees.”

Friedman is the Director of the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University, a 281-acre preserve in Boston, part of the 7-mile-long network of parks and parkways that Frederick Law Olmsted designed between 1878 and 1892—the Emerald Necklace. The Arboretum is home of one of the world’s most comprehensive collections of temperate woody plants—and a treasure trove of trees that originated in China. “Scientists will say, they have to travel all across China to see these species,” says Friedman, “but they can see them all here in an afternoon!”

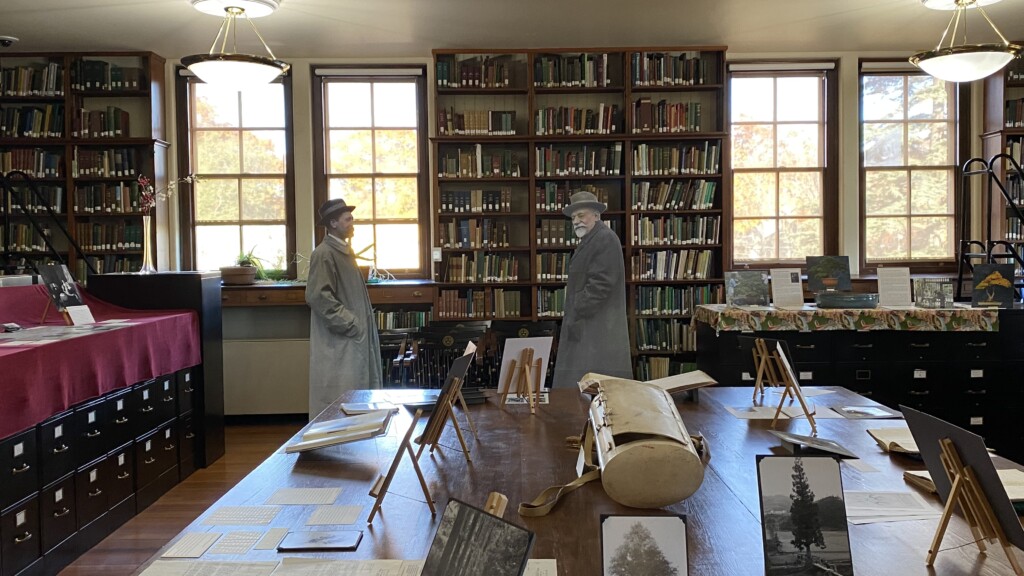

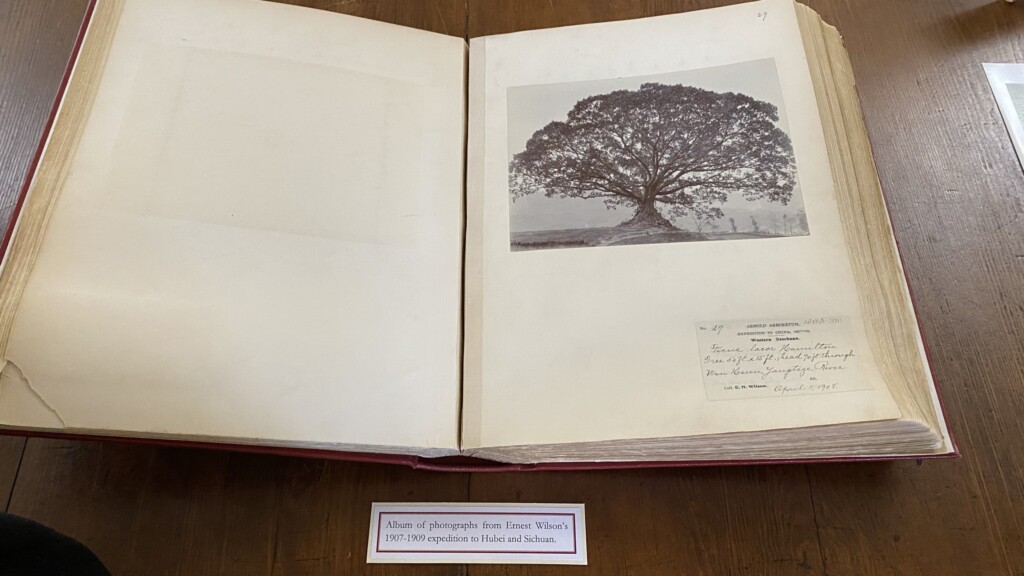

The Arboretum’s China connection began in 1907, when the British plant collector and explorer Ernest Henry (E.H.) Wilson was hired by the Arboretum to launch an expedition to gather botanical specimens in China. Over the next three years, Wilson traveled hundreds of miles gathering plants and seeds in Hubei and Sichuan Provinces, with the help of a team of Chinese collectors. In the coming decades, many others from the Arnold Arboretum would follow, exploring other temperate parts of China, including the botanist and explorer Joseph Rock. After decades of waiting to return to China, the Arboretum joined the first Sino-American Botanical Expedition to China in 1980, and in more recent years, Arboretum experts have traveled across China together with Chinese botanists on numerous academic exchanges—including the one to Wudang Shan in 1994.

Today, the Harvard China Fund supports ongoing research on Chinese biodiversity and collaboration between Harvard and Chinese botanists who are working on studying, documenting, and preserving the flora of China. “The funding has been instrumental to support our recent initiatives. By directing funds specifically to our work [in China], we’ve been able to maintain our current relationships, as well as expand them to other institutions in China,” says Michael Dosmann, Keeper of the Living Collections at the Arnold Arboretum. He adds that funding from the Harvard China Fund has measurable impact on the preservation of Chinese flora. “And indirectly, the support has been crucial in nurturing a network of collaboration that goes back over a century. These may be a bit more challenging to measure and quantify, but they have no less meaning.”

COVID and worsening U.S.-Chinese relations haven’t stopped that collaboration—despite the difficulties in international travel during the pandemic. Chinese botanists continued to collect, and even last year they sent seeds to the Arboretum, “including an unusual elm species that we didn’t have before,” says Friedman. “We have seen no change” as a result of political tensions. “When you have two scientists staring at a plant, everything is simple: we speak the same language, one that is rooted in a deep love and appreciation of the extraordinary biodiversity of China. Indeed, our shared passions to document and study the woody plants of China rise above all politics.”

Our conversation is interrupted by the arrival of Richard Primack, a world-famous conservation biologist at Boston University, who is walking the trail in an Indiana Jones-style felt hat. He tells us he is studying the leaf senescence, or seasonal (fall) aging, of various trees. Primack is working with Chinese scientists at the Beijing Botanical Garden and elsewhere to track leaf-out, leaf-fall, and fruiting times. “We are looking at how climate change is affecting things,” says Primack. “I will share these data [from the Arnold Arboretum] with [colleagues in] Beijing.” Have U.S.-China tensions affected his work with Chinese scientists? “The opportunity to get to know each other is so important. We don’t even think about politics,” says Primack. “We just want to understand the natural world and the changing world. We are looking at issues of great complexity. Plants transcend everything.”